I received today a citation to a patent application, US Pat. Pub. 2006/0259306, entitled, “Business Method Protecting Jokes.” This was filed as an international (PCT) application by an English patent attorney, who told an interviewer that his purpose was “to test the bounds of patentability around the world.”

I remember vaguely hearing about this when it was filed. Given that it has been a few years, I thought it would be interesting to see how the PTO examined it. So I looked!

Claim 1 as proposed in the application was: “The process of protecting a novel joke which comprises filing a patent application defining the novel features of the joke.”

The first office action (made in mid-2008) rejected the claims for many reasons:First, the office rejected the claims under Section 101 (lack of patentable subject matter) for:

- lack of utility

- not within any of the 4 statutory classes (a “joke” is not a machine or a process, etc.)

- as to certain claims, because they claimed “printed matter” or “nonfunctional descriptive matter recorded on some computer-readable medium”

Second, the office rejected the claims under 112(1) because one would not know how to use the invention, given it has no utility.

Third, the office rejected the claims under 112(2) for indefiniteness:

- claim 1 referred to “a novel joke,” and the word “‘novel’ is subjective” — see more on this below.

- claim 10 (dependent) referred to unclear terms “partial skill of animals” and “preferably.”

- claim 22 – “metes and bounds cannot be reasonably determined” – the claim said, “A process claimed in any of claims 1-7 in which the patent application is filed, or claims priority from an application that is filed, on 1 April,” and a comma at the end was used instead of a period. I’m not quite sure what confused the examiner about this claim.

- claim 23 – the claim said: “A homoproprietary patent application or patent.” The rejection said that the meaning of “homoproprietary” was unclear, and that the definition in the specification, which the examiner thought meant “claiming itself” was not clear enough. The examiner observed that all applications must claim subject matter within the specification, per section 112(1) and (2), hence must in a sense “claim themselves.”

- claim 24 (dependent) – reference to “application” was unclear.

- claim 25 (dependent) – claim didn’t say what elements were in the referenced “kit of parts.”

Fourth, the office rejected the claims under 102 (anticipation) based on “applicant admitted prior art” because the applicant had written in the specification, “It is known in the prior art to file patent applications which are funny,” and even gave examples. The examiner viewed this admission as anticipating most of the claims, inherently, including independent claims 1 and 23 quoted above.

Fifth, the office rejected the claims under 103 (obviousness) based on the admitted prior art, with the reasoning that, if not anticipated as inherent, it would have been obvious to modify the admitted prior art to “include protecting a joke” because: “such a modification is desirable to a comedian or someone making a living from their comic material.” The examiner marched through the claim limitations, found that the differences from the admitted prior art were “only found in the nonfunctional descriptive material and not functionally involved in the steps recited,” and cited three court cases about descriptive material not distinguishing prior art.

At the end, the examiner included a several-page discussion, complete with cites, on claim construction and when an applicant must provide information to say he is trying to be his own lexicographer, and also alerted applicant that he should say if his claims are intended as product-by-process claims. These might have been form paragraphs for this examiner.

In all, I thought that this was a very nice job by the examiner, whose name (to give him credit) was Jacob C. Coppola. People often accuse the US patent system of being “broken,” but I think this episode proves quite the contrary: Even though the application was done as a parody and without serious intent to obtain a patent, the PTO took a careful look and made a set of reasonable rejections. The applicant did not respond to the office action, causing the application to become abandoned.

The only part of the rejection that caused me to raise my eyebrows was the 112(2) rejection on the ground that determining something is “novel” is merely “subjective.” If that is true, then all examiner 103 rejections are “subjective,” despite cases like KSR, where the Supreme Court said that common sense should be used to determine obviousness.

Coincidentally, just today, I spoke to an examiner about a Section 101 rejection, and in the course of expressing his frustration about having to determine what is “significantly more than an abstract idea,” he said that he was inclined to make a Section 112(2) indefiniteness rejection of the Supreme Court’s opinion in Alice v. CLS Bank, the most recent opinion on “abstractness.” I hastened to agree with him on this point! Shouldn’t Supreme Court justices be held to at least the same standards of precision as patent applicants?

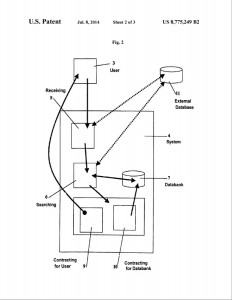

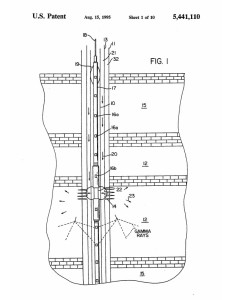

On a related topic, I noticed also U.S. Pub. App. 2008/0270152, where the large company Halliburton applied for a method relating to making a claim of patent infringement. The main claim, in summary, relates to securing an equity interest in a software patent (or application or concept) developed by someone else, using a computer “to convert a first unobservable aspect of the product of the [infringer] to an observable aspect” (i.e., reverse-engineering a trade secret using a computer). Then the owner makes an inference about the trade secret, writes a patent claim in the patent property to cover the inferred trade secret, files and prosecutes the application to get a patent, offers a license, and tries to obtain a settlement for infringing the patent.

Apparently Halliburton hoped to obtain issuance of this patent and make counterclaims against “trolls” who accuse it of infringing patents.

The examiner rejected the claims under 112(1) (new matter in claims), 112(2), 101, and 103, the obviousness rejections being of several types relying on a variety of articles on patent assertion, “trolls,” and trade secrets, plus the USPTO website.

Halliburton received a final rejection and appealed to the USPTO Board of Appeals. The matter is fully briefed and awaiting decision by the Board for about two months. Given the pendency, I won’t comment on the rejections. We should have an answer from the Board in about 2018 or 2019.

Happy April Fools’ Day!

P.S.: Everything in this post is completely true!